Resources

Firm Insights

Trademark Tales: Covfefe® Really?

A lexicographer’s task of pinning down a word’s origin can often mean hours, and even days, of ink-stained research drudgery. But when it comes to one particular word, even we non-lexicographers can identify the precise time it entered our lexicon: 12:06 am on May 31, 2017.

At that very moment, the President of the United States a/k/a Tweeter in Chief, hit Send for the following message: “Despite the constant negative press covfefe.”

Yes, covfefe.

(Instagram/@kandypinkard)

To say that this mysterious new word went viral is an understatement. A Google search for “covfefe” turns up more that 14 million hits. And, of countless “covfefe” memes. As our Tweeter in Chief might say, that is HUGE.

And for those of us ensconced in that legal niche known as intellectual property, evidence of that HUGE response now sits in plain view among the trademark application records at the US Patent and Trademark Office. The “covfefe” tweet went out just after midnight on May 31st. By the close of business on that same day ten trademark registration applications had already been filed for COVFEFE. Those applications sought registration of the word as a brand from everything ranging from beer to T-shirts to coffee to—ready for this?—“advice relating to investments.”

The number of those applications has now grown to 34. Most are for just the word mark COVFEFE, although my favorite—Serial Number 87471677–turns the mystery word into an acronym for: “Carry on Valiantly Fighting Evil For Ever.” That applicant, one Patrick Thompson of Mississippi, hopes to use the trademark, according to his application, “in sales of a variety of apparel, mugs, bumper stickers, and other merchandise.”

Trademark Tales: 2016 Election

COVFEFE is hardly alone. The past election year spawned other unusual trademark registration applications. For example, during one of the Presidential debates, an angry Donald Trump referred to Hillary Clinton as “nasty woman.” There are now 20 applications to register NASTY WOMAN as a brand, and one has already been granted for “scented body spray.”

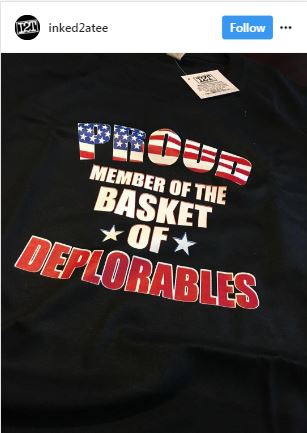

(Instagram/@inked2atee)

During that same election season, Hillary Clinton made what she believed was an off-camera reference to Trump supporters as a “basket of deplorables.” Three trademark applications followed, including one for apparel under the trademark PROUD MEMBER OF THE BASKET OF DEPLORABLES.

Indeed, this pattern has played out over the years—a word or phrase suddenly becomes popular, and then the US Patent and Trademark Office starts receiving applications. For example, Katy Perry headlined the Super Bowl XLIX Halftime Show on February 1, 2015. During that performance, the missteps by the dancer in the shark costume to the left of Ms. Perry quickly became the subject of good-natured ridicule on the Internet. Within the next nine days, two applications had been filed to register LEFT SHARK.

Trademark Tales: Three-Peat

One of the more interesting, and somewhat controversial, trademark registration strategies was employed by NBA Coach Pat Riley back in 1988, when his company filed an application to register THREE-PEAT for shirts, jackets and hats. At the time, Riley’s team, the Los Angeles Lakers, was on its quest to obtain what would have been a third successive NBA championship.

(Website/InsideHoops)

Although the Lakers didn’t succeed, Riley most certainly did. He eventually obtained several THREE-PEAT trademark registrations, and—according to ESPN—his company collected royalties from sports apparel makers who licensed the trademark for use on merchandise commemorating the Chicago Bulls’ three consecutive championship from 1991 through 1993, and then again when the Bulls won three consecutive NBA championships from 1996 through 1998, and then again when the New York Yankees did a three-peat from 1998 through 2000, and, at last, when the Lakers won three straight NBA championships through 2002.

But those THREE-PEAT registrations raise an interesting trademark protection issue. That’s because the term “three-peat” has entered the English language. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines it as “a third consecutive championship.”

Why is that an issue? Because Riley’s company must now be on guard to make sure his valuable trademark doesn’t die of genericide. Genericide, which allows for cancellation of a trademark, occurs when the public appropriates a trademark and uses it as a generic name for particular types of goods or services irrespective of source. This can occur due to a trademark owner’s failure to police the mark, resulting in widespread usage by competitors leading to a perception of genericness among the public.

Should that occur, “three-peat” will earn a spot in that somber graveyard of dead trademarks whose tombstones include the following once-powerful brand names: aspirin, cellophane, dry ice, escalator, flip phone, heroin, laundromat, teleprompter, thermos, trampoline, and zipper.

The latest genericide target is one of the most valuable trademarks on the planet: GOOGLE. A plaintiff sought to cancel the trademark on the ground that it had become a generic verb for an Internet search—“to google”—and a generic noun for a search engine—“a google.”

The trial rejected the claim, and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals recently affirmed that rejection, explaining:

[A] claim of genericide must relate to a particular type of good or service. In order to show that there is no efficient alternative for the word “google” as a generic term, [plaintiff] must show that there is no way to describe “internet search engines” without calling them “googles.” Because not a single competitor calls its search engine “a google,” and because members of the consuming public recognize and refer to different “internet search engines,” Elliott has not shown that there is no available substitute for the word “google” as a generic term.

As for “covfefe,” assuming one or more of those 34 trademark applications actually matures into federal registration, their owners’ list of enforcement tasks will not include, at least in the near future, fending off genericide. That’s because, as the Ninth Circuit explained, a trademark first needs to acquire a generic meaning before it risks loss of its trademark protection. Try to look up the definition of “covfefe.” According to the Collins Dictionary: “covfefe means covfefe.” It adds the following note: “mentioned in a tweet by Donald Trump – presumably a typo, probably for ‘coverage.’”

Of course, it’s no fake news for the Donald to claim his own version of a three-peat in the realm of coined words. That’s as easy as, well, “Lyin’ Ted,” “Little Marco,” and, of course, “covfefe.”

The choice of a lawyer is an important decision and should not be based solely upon advertisements.

Let's Work Together

If you have questions, we’re ready to help you find the answers.

Newsletter Sign-up

Join our mailing list and stay up to date with Capes Sokol!

By clicking the “Subscribe” button you

agree with our Terms and Conditions.